I planned to have breakfast at Ikiikitei, a seafood bowl specialist shop at Omicho market. Kanazawa is on the Sea of Japan coast and has access to some of the freshest fish in Japan, seafood bowl is a common cuisine in Kanazawa.

The shop opens at 7 so I had the bread and coffee bought the night before first.

When it came time to go, the Machi-Nori bike dock terminal refused to operate. Not in service, it kept saying. After a few goes, I checked the service website, to discover that the bike does not operate before 7.30.

Why? Maybe system maintenance. Whatever the reason it meant I had to walk to Omicho Market instead.

It’s only 600m to Omicho so I was not too bothered by this. When I got there however it took me a few minutes to find the small restaurant.

Tucked away in one side alley, the shop was so small it only had maybe 10 counter seats. I had to check twice to be sure I had found the place.

Seafood can often be a bit pricey, often 3000Y or more, and having so much raw seafood in the morning can be overwhelming. Here they serve a mini-bowl option for just 1500Y, and if one wasn’t choosy even a 800Y bowl of the day choice.

I squeezed in and found a seat. The place was not crowded but also no shortage of customers as several streamed in after me.

The chef held up a bowl, asked me how much rice I’d like. The normal portion, I answered.

The portion was more than expected, a dozen sashimi slices of various fishes whose name I had no hope of recognizing, a leg of octopus and a prawn. There were even gold specks decorations on top, as everything in Kanazawa are obliged to have.

The seafood was very fresh, though not particularly notable compared to the rice which were quite flavourful.

Afterward I head to Higashi-Chaya area, the most historical district of Kanazawa.

Similar to Kyoto, Kanazawa was spared from air raids in the war and retained many of its historical districts. Higashi-Chaya was once the entertainment quarters in the Edo period. Some of the teahouses here are still in operation and when dusk falls the district takes on a different atmosphere and the sound of music reverberates behind screened windows.

Higashi-Chaya is situated to the north east of the castle, a quick 5-10min ride from Omicho. The Asano river separates it from center area of Kanazawa.

Just before crossing the river, on the south bank was another former tea district called Kazue-Chayagai, smaller in scale and fewer historical buildings. It distinguishes itself by being on the riverfront with a bank of cherry blossoms. The alleys are tight and there are several restaurants tucked away in its backstreets.

Underneath the blue sky, the cherry blossoms greeted early tourists energetically. The night’s rain had barely dimmed their luster, only a few fallen petals laid on the ground.

I followed the river south, crossed at a small bridge then circled about the other bank to the direction of Higashi-Chaya.

It was still early and there were few people about. Unfortunately the various shops also took this hour to load/unlock inventories so there were many cars and vans going to and fro on the main street, making a clear shot for the camera difficult. It was still too early for the preserved teahouses to be open, and I spent some time wandering the quarter first.

Despite being the largest of Kanazawa’s three Chaya districts, Higashi-Chaya is still only about a hundred twenty meters in length, consisting of a main street and three other side streets in parallel joined by connecting alleys.

Toward the back of the quarter I run across a shrine, the Utasu Shrine. Nestled on top of a small flight of stairs, within the grove of tall cherry blossom trees, the tori and hall’s roof of the shrine peeked from behind canopies of flowers like geishas behind standing screens.

The shrine was empty other than the lone security guard who swept the grounds dutifully, oblivious to the scenery he was a part of.

It felt appropriate to give a little offering. While I loitered around a pair of teenage couple came up, awwing and taking photos of each other.

When I circled back to the main street the chaya Shima has opened.

Shima is one of the best preserved teahouses in the quarter, retaining much of its original furnishings from when it was built in the Edo period.

Like other teahouses Shima is a two level construction. Two storey buildings are a rare sight for houses of this period, houses for commoners were only permitted to have a single storey, teahouses were one of the few trades that were exempted from this restriction.

After paying the 500Y fee at the entrance, the guide route goes upstairs on a narrow flight of stairs. The top of the stairs opens up into the main entertainment room that connects to three other rooms where dances and music were performed to entertain guests. None of the rooms were very large, the largest at best 5 or 6 meters wide and could not have seated more than a handful of people, and the dances would have to be performed with the smallest movements. Sound from other guests would also surely have been major issue, the rooms separated only by paper doors. To me it was hard to imagine what entertainment could be had in these narrow confines.

I can only reason, in a time when travelling to a shrine at the foot of the distant mountain constituted a pilgrimage, the world must be a smaller place. And perhaps, the small confined space adds to the intimacy creates the feeling of being a world apart to the outside.

The teahouse characterized much of what I’ve come to understand about pre-modern Japan. The plainness, the carefully measured layouts. The small details in the corners. The seemingly nonsensical way the rooms connected. When the high class room had its wooden frame and pillars lacquered in luxurious red and the best regarded room had translucent paint to bring out the natural grain of the rare timber used.

Above the alcove and doorways hung faded ink paintings that for time ageless bore witness to the coming and going of samurais and merchants till the light of its abode faded and the wealthy patrons were replaced by the curious.

The facilities of the teahouse were housed on the ground floor, well preserved. Toward the front was the owner’s living room, the office where cash books were kept and recorded the spending and bills for patrons and salary for the courtesans, some of these books were on opened on display, the writings difficult to decipher. In a small room facing the street the room was crowded with shelves displaying the tools of the old trade. Instruments and hair pins, ceramic and lacquer wares of most exquisite workmanship. Magnifying glass were provided to study the fine lines and details drawn or etched on the surface.

Toward the back was the old kitchen that saw the creation of many fine dishes on the woodfire stoves. There was a well and beneath the stairway an underground cool store used to keep ingredients fresh in the hot summer months. At the far back of the ground floor was a teahouse where one can have traditional matcha and sweets while appreciating the small Japanese garden.

I did not see the signs till almost finished touring, that photo using mobile phones was allowed.

The street had come to life, the blue sky backdrop to the verdant painted wood.

A pair of to be wed stood posed before praising eyes of DSLRs. Shuttered doors opened to welcomed customers.

The second teahouse, Kaikaro, still functions as a geisha house in the evening. At night it received selected guests only, in the day the mystic was lifted and the place opened to the curious public.

Kaikoro was at least three times the size of Shima, laid out in similar fashion.

The interior was better maintained, even possible to describe as glamorous in places. In the tokonoma hung well painted scrolls of flowers and birds. The rooms contrasted with luscious red and deepened blue.

There was also a cafe within the teahouse with slightly more expensive menu.

The pride of Kaikoro was a room of literal gold. The threads of the tatami was woven with gold threads and the timber lacquer laid with gold leaf. When I had read about it initially I had imagined the epitome of bourgeois opulence; lavished crudeness of riches as shallow as the gold leafs. In person it was actually quite fitting of an aesthetics to be expected of Japan, the golden tatami reflected in a unremarked regal light, reserved with hint of splendour visible just beneath the surface.

After Kaikoro I wandered around some more. There are many cafes and other small shops in the area, most numerous were the gold leaf shops. Every craft workshop had to have a presence here of course.

The smaller souvenir shops held works from less known workshops, some possibly even unknown ones that might well have been imported from China. They were also very souvenir looking and didn’t earn more than a glance from me.

There were two gold leaf shops of note on the strip however. Hakuza Hikarikura and Hakuichi.

Hakuza Hikarikura is the more trendy and modern shop with many jewellery and accessories, gold leaf wine (which gave me pause and many questions as to why) and bags and lacquerwares. What makes it worth the visit though was that it boasted a gold leaf plated kura or storehouse, thus the name of the place. The kura was not as well lit as it might have been and the lustre cannot be compared to the golden room of Kaikoro.

Hakuichi on the other hand is very traditional with a strong focus on craft. The Hakuichi has several shops around the city and it hosts workshops that lets tourists create their own gold lacquerwares. During planning I had been very keen to book a workshop but ultimately could not because of time constraints.

The place sold gold leaf ice creams, many fine lacquerwares, gold leaf cosmetics and other art items, such as paper fans and even small armor sets. I had my eyes set on a series of ukiyoe printed on gold leaf (or gold leaf as one layer of the ukiyoe print, could not really tell which). I really wanted to buy it but failed to decide on the spot. There was still tomorrow, I told myself. Plus if I buy it now it might get wrinkled in the bag. There’s a shop at the station, it’d be better to get it there.

Hakuichi is without doubt the more interesting of the two. And I spent a long while there looking through the various items.

I headed to the gold leaf museum, on the edge of the district by the side of a busy road.

Officially called the Kanazawa Yasue Gold Leaf Museum, it is the only museum in Japan dedicated to gold leafs. Named for a gold leaf artisan Yasue Koumei from the Meiji period, the museum contains a gallery showcasing the history and process of gold leaf making in Kanazawa, as well as exhibition spaces displaying various art items utilizing gold leafs.

The exterior was an unremarkable building with black claddings with gold linings and letters. The entrance might well have been mistaken for the local library, with little fanfare or signage.

As I have come to expect of most traditional museums the place was completely empty. The two front desks were genuinely surprised when I asked for the musuem daily pass, a pass which for just 510Y granted access to many of Kanazawa’s museums and art galleries.

The first floor was a multi purpose exhibition space that was playing some Kanazawa tourism videos. I headed up stairs to the main gallery.

The first section was about the history of gold leaf in Kanazawa. The text was quite dense which proved challenging, the timeline seemed to have skipped over some details as some seemed contrary to each other. One thing for sure was that the development of gold leaf making in Kanazawa was a much more recent development that the image the city would like to portray. Though that was true for many other things in Japan. It’s easy to forget that many traditions, especially those outside the home provinces were not formed till the Edo period.

As the foundation of commerce and wealth, gold leaf making was of course a restricted trade in the past, controlled by the shogun.

Toward the end of the Sengoku period Toyotomi granted the lords of Kanazawa the right to create silver leafs. The records weren’t clear but gold leaf making in Kanazawa likely began at the same time. In the early 1800s gold leaf artisans were brought from Kyoto to supply the material needed to rebuild the burnt down castle buildings. After that there were several periods where gold leaf making was banned and this was where the descriptions get vague, but the implication was that the craft continued in some capacity through out.

During the Meji period gold leaf making grew and out of a need to control quality of gold leaf produced in Kanazawa an association was formed and the city began to dominate gold leaf production in Japan.

The growth brought by industrialization went into decline with onset of war, luxury items were severely curtailed and the craft would not see its rebirth till the 1960s. Even then with rise of foreign imports the gold leaf making trade continues to struggle.

My impression was that Kanazawa became renowned for gold leafs more as a matter of being the lone survivor in Japan than any extroadinary heritage, and its image was somewhat a modern invention.

The next section introduced visitors to the process of gold leaf making. Where rough sheets of gold was bound in leather and special paper then beaten under a machine repeatedly, the bundle moved and adjusted by the hand of the craftsman. Then the gold leaf would be trimmed, rebound and put back under the machine. Beating, trimming and rebeating until the gold leafs were so thin a light breath sent ripples across its surface; yet the thin sheet holds, exhibiting the remarkable strength and elasticity of gold.

There were also interactive displays to show the weight of gold compared to other materials. Some explanation of the different metal mix of gold leafs and their colour. Some had more silver, others a little copper, brass, zinc.

The edible gold leafs added aplenty to every kind of food here were ones without addition of copper. Gold alone was very stable and when digested would simply go through the digestive systems without being absorbed by the body.

The third hall hosted some rare items utilizing gold leafs. A golden threaded Noh play kimono, statues of Buddha laid with gold and of course various lacquerwares.

The museum was comparably small, perhaps a little light on details. I would have liked to have seen some videos of how gold is applied in various crafts.

After this it’s whirlwind tour time. Kanazawa had so many places to see and time was compressed due to the cherry blossoms.

First stop was the Kenrokuen again, having been foiled by the rain yesterday.

The sky was clear and people crowded into the teahouse row and garden. It was early 11am, not quite lunch time but thinking about the schedule it be more efficient if I grabbed something now. It meant skipping the original sushi train lunch plan at Katamachi but I’ve never had reservations about trading food for time.

I got a yakisoba from one of the festival stalls. Just as it’s not a market without a grilled sausage in Taiwan, in Japan it’s not quite a festival without having some yakisoba.

I had my little own Hanami. Sitting on a bench beneath a blue sky and pink blossoms. The heavy taste in the mouth. People walked here and there, some had sticks of cornknobs or squids, other had the all famous Kanazawa gold leaf wrapped soft cream.

Back at the Shima there were discount coupons to the teahouses outside the garden, of which I had taken a few. 80 or 90Y off the price of a soft cream, and I opted for the kind with a sprinkle of gold and not one wrapped with an entire leaf. Gold itself had no taste. It’s the novelty factor. Looks good in the photos.

I took a brisk stroll across the garden, looking at reflections of cherry blossoms on the surface of the pond and streams.

It was not as large as Korakuen in Okayama, but much more intricate. With small twists and turns and groves of trees and moss. It might be a benefit of being situated on top of a hill and able to take advantage of the elevation differences. The scenery was ever changing as one wanders through the grounds, as opposed to Korakuen which was very spacious and open.

Descending the slope to the 21st century museum, I took a bike toward the west side where the old samurai district called Nagamachi was.

The main thoroughfare between the 21st century museum and the old samurai district was Korinbo/Katamachi, Kanazawa’s main retail precinct with several department stores and shopping complexes packed in close proximity. I biked around Tokyu Square, the road followed along the Kuratuki Canal, one of several canals that once supplied the city with water, for drinking, for fighting fires, for driving mills and machines. The many canals were vital to the city’s development up till early modern times.

Then turning further west, I continued till the road ended after crossing another canal, the Onoshou Canal. Right at the intersection was the Kanazawa Shinise Memorial Hall. Shinise roughly means old store. An establishment with a history, a shop or trade that has been in business for generations.

The Shinise Memorial was once a medicine store belonging to the Nakaya family. The family first established a traditional medicine shop back in 1579 and was given the honor of supplying the local daimyo with various remedies. The shop has since been moved a few times, with the current merchant house built in 1878 in honor of Emperor Meiji’s visit and later donated to the city in 1987.

The place retained much of the original layout and feel of the Meiji era, with very wide storefront with shutter doors that could open the house to the outside.

The entrance was via the side through a small gate. There’s an 100Y fee. An amount that might as well be a donation when an average temple might ask for 300-400Y. Not that it mattered being covered by the one day pass.

The middle aged man stamped my day pass (which after 3 or 5 could be traded in for a small souvenir) and welcomed me with a smile and explained that everything can be photographed.

I was not the only visitor; there were footsteps upstairs. Though for the time I was alone on the ground floor.

The tour path began at the store front area where customers would have come up to ask for a remedy for their ailments. The store area itself was on raised tatami but customers could approach and wait at the doma, the dirt floor before the raised area. The doma actually goes all the way around the house so people could access most of the ground floor without needing to remove their shoes.

On the shelves were packets of drug prescriptions named for powerful sounding than efficacy. Kidney and heart pills, pill that cures ten thousand illnesses. There’s a strange number of Kougentan, a secret recipe that roughly translated meant mixing of essences.

On the wall hung many other labels of divers drugs, the symptoms they treated and boastful claims of efficacy. The simple design and bold lettering declared the simple and hopeful period they were from.

The next room was the medicine store where prescriptions would be grounded and mixed with the various tools displayed.

Around the back was the guest room where guests were welcomed with hot tea from the pot hung over the hearth. Now doubling as a makeshift display room for shelves of Kaga temari large and small. Yarnballs, a local traditional craft. Traditionally they were toys for children, now they also serve as talismans for good fortunes. Intricate woven balls of brightly coloured silk strings, the balls glistened in the light much akin to christmas tree baubles. Some were small, the size that fit comfortably in one’s hand, some big, the size of a bowling ball that were assuredly for show than use.

Going upstairs. The level above was devoid of fixtures or decorations. Rows of glass displays presented the works of other shinise of Kanazawa. Prints, dye houses, gold and lacquer works. Candy shops; behind a large glass cubicle sat a dense ikebana where the stem and petal of every flower were crafted of sugar.

The shinises were proud, but through the dull, almost historical displays, there was also a trace of sadness.

At an angle opposite the shinise museum was the Maeda Tosanokami Shiryokan Museum, the Museum for the Records of the Maeda Tosanokami family. The family was a chief retainer of the daimyo (actually direct sibling, but I’m not sure if it’s a branch family), one of the Eight Family of Kaga. The Eight Family was so called as the most important retainer family of the daimyo holding the highest offices and positions in the Kaga domain, each receiving an annual stipend of over 10k koku, the foremost Honda family even receives over 50k. The Maeda Tosanokami family received a stipend of 11k koku for most of the family’s time as one of the Eight. Through the generations accumulated huge stores of valuable documents and items. These are now made available in the museums on a rotating basis. The collections so large that even with 4 rotations a year it would take years for all the items to be shown.

The reception stamped my pass then to my puzzlement, began tearing off the stamp collection. There’s a souvenir for collecting three steamps, she said.

I had thought five stamps were needed, did this mean there was a bonus one at three stamps? But then why was she tearing the stamps off.

Perhaps noticing my confusion, she stopped and asked if I planned on visiting more museums. To which I answered that yes, I was planning on visiting the Noh museum and Suzuki Museum.

Oh, was the reaction. She further explained that there were different souvenirs for 3 or 5 stamps, and if I wanted to I could exchange the stamps now, otherwise I can wait till I had collected 5 of them. I preferred the small notepad one got for 5 stamps. The lady found some tape and helped put the stamp card back.

The first floor housed the permanent exhibition introducing the Maeda family. No family showcase can go without a set of armour and sword of course, and here they were displayed in utmost honour and respect, flanked on all walls by the family’s treasured art works.

The back of the first floor opens up into a garden viewing room, a space with some benches that offered an excellent view of the Japanese garden. I dwelled here not. The room was walled in with glass and the aircon exceedingly weak making the place rather stuffy. The garden while beautiful, was not something of spectacular worth beyond what I have seen elsewhere.

The second floor was where things became interesting. The articles of the museum, because of their nature of being items passed down within the family, were not necessarily glamorous paintings or ceramics; books and scrolls that were near impossible to read were a plenty, not only because of the florid calligraphy but also the use of old formal prose. The contents, with some helpful translating to more modern Japanese vernacular, actually were quite illuminating and as I would find out later, helped provide much needed perspective into the next few attractions I was going to visit.

The rotating exhibition at the time of my visit was given a spirited title, Kaga Domain’s High Ranking Samurai, Income’s Uses and Expenditures, Money is Needed!

In the Edo period a daimyo kept the service of many retainers. Each were given a stipend measured in bushels of rice, the currency of the day. A low level officer might receive a couple hundred bushels while a high level retainer like the the Maeda received tens of thousands.

The Kaga domain was renowned for being a domain of a million koku, giving some idea of the economic powers and the number of retainers that could be afforded.

In the days a koku of rice was roughly the amount of rice needed to feed one person for a year. By that measure even a few tens or hundreds of bushels sounds like a large fortune. And it probably was in comparison to the common farmers toiling in distant fields who were one bad harvest away from starvation, but for the samurais the stipends by no means guaranteed a life of luxury or even one without worrying about making ends meet.

As a samurai and a member of the ruling class, certain expectations were required if not by law then by customs. One was the number of clerks, guards and other servants one was expected to keep; the daimyo had high level retainers who themselves had retainers, a pyramids of people serving ones above.

A samurai’s position also demanded a level of fineries, lacquers, kimonos, other exotic items for ceremonies and parties, all of which had to be bought and kept up to latest fashion.

Then there were other expectations such as horses, armours and gears one had to make available for one’s lord at a moment’s call.

Worse still, rice was a poor means of storing or transporting wealth, one could not reasonably cart about and pay with hundreds of bags of rice so a samurai had to convert his stipend into cash with the merchant class who charged huge margins for the service.

What seemed like initially immense fortunes quickly dimished into mere pittances and many samurais struggled to make ends meet. Of course compared to the rural villagers the samurais, even the lowest ranked ones, could hardly be called poor. But many must have wondered about the lavished life their urban artisan and merchant compatriots lived.

Coins, ledgers. There were letters too, of mundane communique between the lord and his retainers. Written in prose whose meaning could only be glimpsed through modern translations.

Japanese today is quite subtle, often a person’s meaning is couched in coded words that takes care to pick out. These letters however are on a whole different level of formality and one must be excused for coming to entirely different understanding at first reading.

Together both museums took near an hour to go through at a steady pace without pause.

From here I walked north along the waterway. The area was the so called samurai district where those who served the lord used to live and the houses from those days remained well preserved.

The walls were a yellowy earthern colour, unique as I have seen in Japan thus far. The impression was softer and richer, refined, markedly different from the ashen white that defined the image of traditional urban landscape.

The streets were narrow, enough to let two palanquins pass by. One could imagine samurais of rival clans squaring off in the narrow confines and rounding the block to surround their opponents.

Some of the houses had signs requesting considerations while others had been converted to workshops or tea houses selling souvenirs and sweets.

There were three main attractions in the area. The first was the Nomura residence, belonging to a samurai of note on a stipend of 1100 koku. When I got there a tour group of european happened to be lining up outside waiting to go in. I continued on, to visit on the way back with hopefully less crowd.

The second was the Takada House formerly belonging to a mid ranked samurai on a 550 koku stipend. The main residence was long gone and only the garden remained, and a long house gate restored and maintained by the Kanazawa city. Given there was only really one building with two rooms, the city perhaps decided charging any paltry fee was more trouble than it’s worth and left the place open for all to wander freely.

There’s only the long house and the curator cleverly made the place be about the servants instead of the masters. The long house gate had the gate at its centre. On one side was a stable and store room and the other was the servant’s waiting room, a space of a few tatami with a firepit at the centre for staying warm in winter and preparing their own meals.

The servant’s job was to see to their master and accompany them when their master go to their offices and attend to their lord. When receiving their master they were to bring out their master’s shoes and throw it before them. Neither rude nor disrespectful, it was a show of being in awe of their master’s superiority.

A samurai had a duty to maintain soldiers for his lord, the numbers differed based on the period and stipend, as an example, a samurai of 500 koku had to provide 2 swordsmen, 1 spearman, 1 archer and 7 servants. So though on the surface a stipend seems a lot, the whole household suffered in poverty.

The garden of the former residence was of little value, only a small pond and few shrubberies.

The third attraction was another block away, called the Ashigaru Shiryokan Museum. A set of two small houses of the lowest rank samurais on just 10 to 25 koku. Although there were no obligations on them having to provide additional servants and soldiers so they might not have been much worse off than a low to middle samurai.

Each house belonged to a different ashigaru household, Takanishi and Kiyomizu, each standing on their own plot of land separated by low hedges and small gardens. They were larger than I had expected from warriors one rank away from peasant; supposedly Kaga’s wealth meant they could afford such spacious housing, in the capital an ashigaru would live in cramped rows of adjoining townhouses.

Roughly divided into two rows of three areas that formed the formal areas and living areas, the house felt spacious and comfortable. On the left was the entrance way and hallway, depending on the layout there may be a small room with a small hearth, perhaps as a waiting room. Toward the back was the formal room which opens up onto the engawa adjoining the garden, granting beautiful bright vistas. On the right side was the kitchen, the chanoma (room for tea, but perhaps closer to dining/living space), the private storeroom or sleeping room.

The rooms were of fair size, the windows and engawa let in plenty of sunlight, the air was fresh and cheery.

One of the houses was unattended and was mostly empty except for a few signs explaining the lives of the ashigaru. The role of the ashigaru in the strongly hierarchical edo society placed them squarely on the lowest rung of the ladder, serving the most mundane tasks of the bureacracy. A household of six nominally would need six koku of rice alone, not to mention other expenses such as soy, salt, wine and other basic necessities. With just 20 koku over half of the income would be spent on food alone, add in other household expenditures then they would barely scrape by. Ashigaru often took up other occupations and produced handicrafts at home to supplement their income.

The other house had a small office. The two houses had no entry fee so there was no need for a ticket window, the office probably served as an equipment store and prepare room for when there are arranged guides, otherwise I saw little need for an office. Having an attendant did mean they could furnish the house with scrolls and chests and other items to show how the place might have looked in the past.

In the living room five table trays with plates were laid out, ready for a family meal. The kitchen was stocked with pots and urns. The place felt lived in, cozy, and would not be surprised if some man in kimono walked out from behind the screens and welcomed visitors to his humble abode.

After the ashigaru house I return to the Nomura residence. The group of westerners had not left yet, either that or another group have followed on their heels, for the place was full.

The Nomura residence once belonged to a middle-high ranking samurai whose descendants later sold it to a wealthy merchant. The new owner kept the place well maintained and furthered the house and garden with his own touches.

It was not large, or perhaps it was a trick of the mind with so many people in the house that it could not be helped but feel crowded.

There was an entry fee of 550Y, a little on the high side. But given the other two were free it balances out and I shouldn’t be critical. Immediately upon stepping up the entrance, a suit of armour belonging to one of the Nomura ancestors welcomed guests in very “this is a samurai residence” sort of artifical way.

Round the short corridor with the main attraction of the house the L shaped room that opened onto the pond and garden. The garden was rated as one of the best gardens in Japan, on the same list as Adachi Museum in Shimane and Rikyu Palace in Kyoto, and the house as a whole awarded two stars by the Michelin guide.

Not sure if the house and garden lived up to such high praise.

In anycase the garden was a water feature garden, with the engawa extending directly over the koi pond. The shores were densely planted with moss and short pines, a few well placed stone lanterns provided depth to the scene. A small stone bridge crossed to an island and had a sign asking visitors to stay out. The garden felt a little messy, the barren branches sticking out through pine needles. It might look well in summer.

In the centre of the house was the Jodan no Ma, a special room reserved for hosting the daimyo. The joist and struts featured intricately carved wooden panels, the fusuma doors painted with mountains rivers by a renowned Kaga painter from the Kano school.

Toward the back the house connects with the old kura (storage house), with thick mud bricks and heavy doors designed to protect the contents within from fires that were all too common in the edo era. The kura has been converted into the Onikawa Bunko, a library holding a collection of historical arts and items of the Nomura family. There were many fine katana swords, wall scrolls and other precious objects that gave great insights into the life of a former high ranking samurai, and elevated the collection to one of great cultural significance.

There was a narrow stairway at the side of the house. It was open to the outside at its corner, where a delicately arranged water sprout was placed. Water pooled on the first level before spilling out the spout in a gentle trickle. Moss and fern covered the stone’s surfaces, and to celebrate spring, a length of bamboo with small branch of flower inserted at its middle, was placed across the pool as a bridge and viewing pavilion. The small insignificant decor held my attention more so than the main garden.

The stairs led up to the tea room. The upper floor was added by the merchant to enjoy the garden and highly recommended by many. Access was limited to customers who ordered the tea and sweets set, and there was no time for such enjoyments.

I rounded off the samurai district and its side alleyway. No time could be spared to the workshops and souvenir shops that dotted the area. In hindsight I wondered whether I should have moved Hikone to give Kanazawa the time it deserved.

Anyhow the whirlwind tour continued. I biked through Katamachi down the Tatemachi shopping street, a pedestrian shopping street spawning off the main thoroughfare in Katamachi. It was the foremost fashion and retail precinct in central Hokuriku, full of trendy shop fronts and and modern signages.

It might be the day of the week (being a Monday where many shops closes), the street did not feel as lively as what ought to be the busiest street in Kanazawa, and I even missed the only animate in town because of how inconspicuous it was. Not even a wall plastered with moe girls as one could expect in Tokyo.

The street laid in a shallow north west west to south east east axis. It took me across the south end of the central district and I circled up the east side back toward the museum district.

On the southern end of the museum district was the D.T. Suzuki museum. The bike station was outside a Lawson on the side of the road, still some distance to the museum which was tucked away behind a large parking lot through a mangle of small streets. Signage was poor and I had to check google map several times to confirm I was on the right path.

I had not heard of Suzuki before this trip. Philosopher, zen master, he was apparently quite well known and responsible for advancing zen teachings in the west. Born in Ishikawa prefecture and a celebrated son of the Kanazawa.

The museum was built in the suburb where Suzuki was born and designed to comemorate Suzuki’s life and teachings and provide a place of meditation and thoughts.

True to its zen roots the museum’s exterior was plain and dangerously easy to miss. Simple ashen concrete with well defined right angles. The side facing the courtyard was walled with slit poles drawing inspiration from the slit windows of Higashichaya. Upon entering the hallway was dimly lit, yet where there were windows sunlight shone through brightly, casting long dark shadows.

The museum was included in the museum pass, otherwise entry fee was 300Y. A small folder containing note papers was given to the visitors to take notes and record their thoughts. And I got another stamp on my pass.

Taking photos on the inside was not allowed. The galleries mostly held original works of Suzuki and various quotes of his. The photo ban was most likely to avoid people distracting others’ contemplation than any copyright rules.

At each section of the gallery a small info sheet was available for visitors to add to their folders and their knowledge of Suzuki’s perspectives on life.

A brief interruption came when a man approached with a pad for a quick survey of the origin of each visitor.

The halls at last opened up onto the main water garden feature which the museum complex was built around.

Square in shape, the pool reflected the world about. At its center the room of contemplation rippled, the tower of its roof rising above, breaking the confines of the walled space.

The contemplation room was open on all sides, allowing the cool breeze in and visitors to sit freely and inspect their thoughts in the surrounding water.

It’s doubtful how many visitors use the room for its intended purposes. Of the six or seven people I met during my visit, most, me included, were content to grab a few photos of the reflecting pool and continue on with their day.

I left without feeling tranquil nor insightful. A museum on zen required time I did not have.

Next stop was the Noh museum, bringing me back to the centre of the museum district.

Once again the museum did not particularly stand out and its mostly glass modern construction might be mistaken for a fashion retail. It sits on the main thoroughfare on the same block as the 21st century museum.

I got the final stamp here and traded the collection for a notepad. The Noh museum consists of two floors, with the ground floor area sharing the same space as the reception foyer, fenced off visually only by a tall panel and display cases.

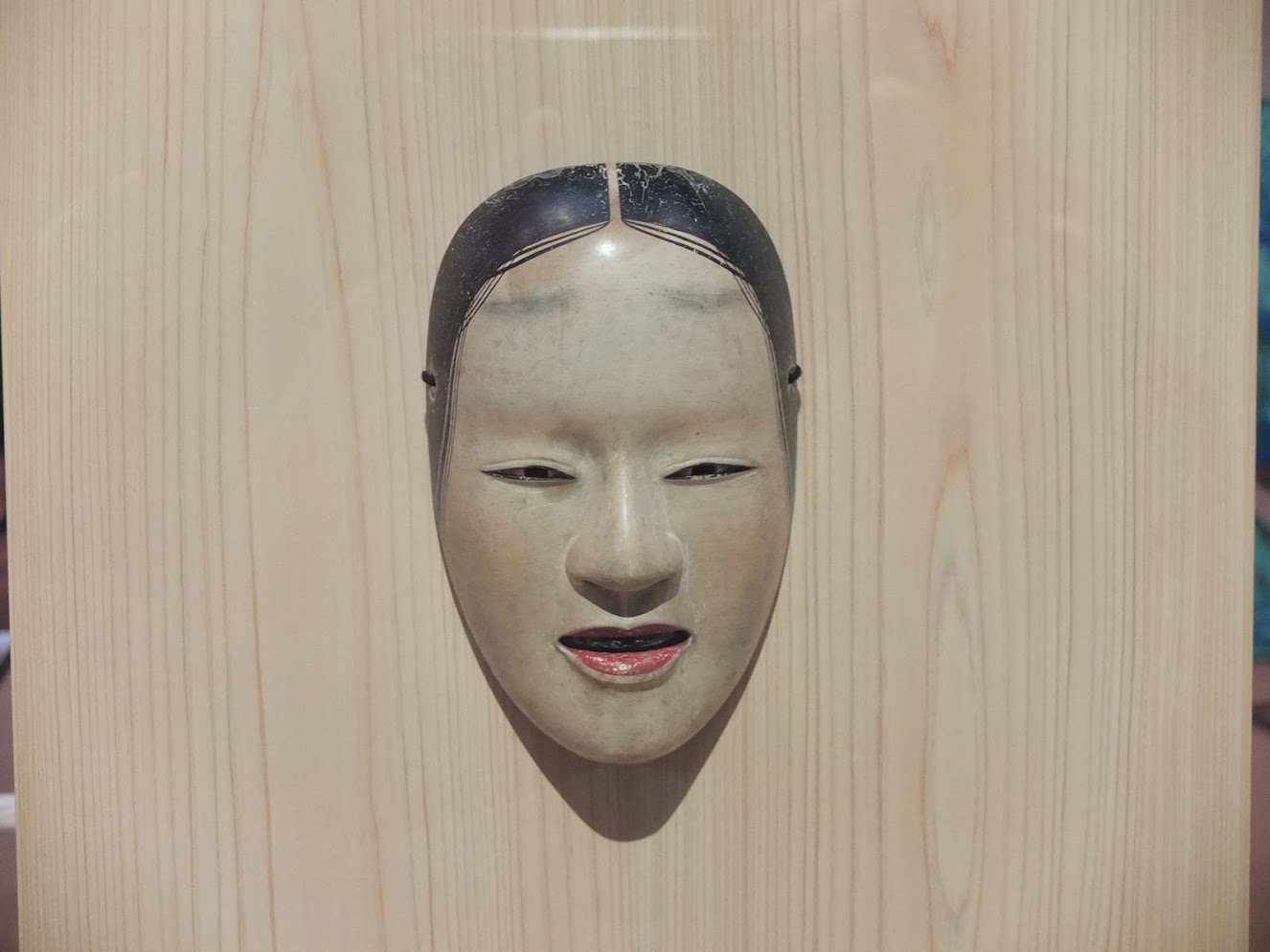

Noh is the traditional Japanese performance for the aristocracy. It mirrors the kabuki which was performance for the commoners. Kabuki is loud, full of expression and outlandish stage props. Noh in contrast is incredibly restrained. A Noh stage is always the same. A stage with posts in four corners reminiscent of kaguya stages of shinto shrines. The backdrop of the stage is always a pine tree, and the entry bridgeway to the stage’s left (from the audience’s direction) is lined with three small pines. The right of the stage sat a band that played traditional instruments while the actors performed on the relatively small stage.

The biggest difference, was that kabuki actors wore colorful makeups allowing them full range of facial expressions, while noh actors wore masks that covered the entire face. In noh, emotions were conveyed through voice, movements and clever positioning of the mask alone. In a Japanology episode, it described noh as acting through movements of the feet. The way the actor lifted his feet, the pace which he stepped, the angle he placed it down. Hesitance, sorrow, excitement, tension, they could all be conveyed by simply looking at the actor’s lower body alone.

Patronized by the ruling class, Noh has throughout the ages sought to distinguish itself from the latest entertainment of the commoners by holding fervently to its original form, resisting changes and continued to be performed in its ancient style as stalwarts of tradition.

The noh play in Kanazawa is of the Hosho school, said to be more abstract in its performances. It later developed into its own style called Kaga Hosho, which became something for even common people after the Meiji restoration abolished the samurai class. There’s a claim that in Kanazawa, noh falls from the heavens, in other words the art was so popular even the common gardener or carpenters sing noh chants while they worked in high places. A doubtful claim; the city positions itself as the centre of traditional culture, second only to the ancient capital and I would not be surprised by a few hearsay exaggerations.

The first section of the floor introduced noh plays. Taking inspiration from the noh stage the area was separated from the foyer by a pine tree wall and framed by four columns, each having the name and purpose on stage.

The column at the back and left, by the entry bridgeway was named the shitebashira 仕手柱, main character’s pillar, for it was the direction where the main character would make his entry.

The column at the back and right was named the fuebashira 笛柱, literally flute pillar, for it was near where the flute players sits.

The column at the front and left was named the metsukebashira 目付け柱, the sighting pillar, for it was an important point of reference for the actor whose vision was limited by the mask. By anchoring himself relatively to the pillar, the actor can position himself to the correct spot on stage.

The column at the front and right was named the wakibashira 脇柱, the secondary character’s pillar, for where the secondary character would sit on stage while the main actor performs.

Around all sides were wait high glass displays showing various items used in Noh plays. Flutes, item of clothing, small props, masks. A few showed tools and methods used to craft the masks.

At the centre of the display area was a miniature model of the noh stage to give a visitor a better idea of what one looked like.

Generally speaking the information offered was rudimentary and did not offer a proper introduction to Noh plays. It felt simultaneously too shallow while assuming visitors already had some notion of what Noh is. To be fair to the museum Noh is not an easy concept to convey and I still grapple with what it is despite having read a few books on it. Noh has the honor of being the oldest surviving form of theatre, a tradition that dates back to the 14th century and far removed from modern sensibilities. The music is rhymetic and slow, the speech difficult to understand, the tales draws on ancient folklores and historical figures, the performances are abstract and requires familiarity by the audience for understanding.

At least it is not court music which is more monotonous than water dripping down a bamboo pipe; at least the later is soothing.

There was an experience area, visitors were welcomed to put on a Noh mask and dress with the assistance of the attendants. The two old ladies there were incredibly enthusiastic and excited by the prospect of a visitor. Clearly they haven’t seen many guests that day or any at all.

Initially I declined, not wanting to go through the troubles. I looked at the clothing and masks by myself. The masks, the surface incredibly smooth and seemingly made of clay and weighty.

“This looks heavy,” I commented.

“Oh no, not at all,” the ladies replied. They seized the opening, “Here try holding it.” They picked one up and presented it to me.

It was lighter than even my lightest estimate. It was made of wood, very very light wood, as though a hefty wind would take it into the air. The mask was almost 7 or 8 mm thick yet weighed maybe a third of what I felt wood of the size should.

“Wouldn’t you like to try putting it on, come, we’ll dress you.”

They nudged me onto the raised platform and presented a choice of two Noh dresses. One orange and another a darker indigo. I chose the orange one.

The dress was not hard to put on, more of a coat then a kimono. When it came to the mask however there were some confusion.

Before this my Japanese had served me well, but here there was a single word that I could not understand and could not guess from its context. I thought they wanted me to do something with the mask but not to put it on.

After a few back and forths the lady finally performed a posture herself. She bowed. Of course, I felt a little silly at myself. In Noh masks were sacred, said to possess spirits themselves and one had to first pay respect before putting them on.

I held the mask face up and gave it a bow, and finally was allowed to put on the mask.

Vision within the mask was severely limited. Coupled with the lack of glasses I was barely aware of my surroundings. I was at the mercy of the two ladies. Who happily led me through a few different poses and paces.

This pose means sadness. They would help position my arms and head. This pose means laugh. And so on.

It is another aspect of paradoxical Japan, where the everyday reserved body languages are traded for exaggerated theatrics.

They helped take a few photos in Noh wear then helped me out of the dress. They apologized for being insistent, which I replied that I had fun too.

The second floor was more museum like. A quiet space with walls of dark velvet set displays. Various masks and Noh outfits hung on the walls. Masks of gods, demons, jesters, courtesans, ministers, monks. The proportions were doll like, yet life like. The gods (some anyway) were kind, the demons frightening. The ministers were stupid and the courtesans sensual.

The various texts outlining the development of Kaga Hosho Noh is a little hard to understand, mostly speaking of lineages and important Noh performers that guided the development of Noh in the region. It’s not clear what distinguishes Kaga Noh from regular Noh, but it was emphasized that it is quite distinct and is recognized as an intangible cultural heritage.

Overall a good fun experience. Even if I did not have the pass, the Noh dress up experience and the numerous masks in display was well worth the 300Y fee.

The Noh museum concludes my whirlwind tour and I was free to make use of what’s left of the remaining sunlight.

There was the 21st century museum. Perhaps the most well known tourist attraction after the Higashi Chaya district. The museum had a series of outdoor arts that was very iconic, such as the room beneath a swimming pool such that it looked as though people walked on the bottom of the pool, a giant dog…

I was wandering through its outer halls looking for the ticket booth, while contemplating whether to spend time here or to go check out the castle grounds, when I was yelled at by some staff. Apparently there’s no single entrance to the restricted area, there’s several hallways and they were all restricted and to pass through required checking one’s ticket. There was no way to cut across the circular museum directly to the ticket booth; the only way was to circle all the way around.

None too pleased getting yelled at for an honest mistake, I decided to skip the museum. The sun was beginning to set and outdoor sculptures are better viewed in a full sun.

I ascended the cherry blossomed slope and crossed the bridge into the castle, properly this time. The castle keep was long gone and only the restored walls and barracks and storehouses stood as testaments to the once mighty lords of the Kaga domain. It was easily one of the largest castle grounds I have seen, exceeding that of Himeji or Nagoya castle. Because of its hilltop position, the grounds were formed of several natural layers.

The bridge from the garden acted as a backdoor for after a double gate it opens directly onto the main San-no-Maru courtyard.

In the distance was the raised Ni-no-Maru inner courtyard encircled by a tall walls and wide moat. On the left the long wall stretched to connect with the inner hon-maru area where the castle keep would have stood hundreds years ago. Not all of the walls have been restored which made the courtyard seemingly divided at random places.

The storehouses open to visits have now closed, and the visitor centre too. I wandered without aim. The visitor centre held a restaurant/cafe, a relaxation room with wide open glass walls for people to sit and view the wide open castle ground. The history of the castle was plotted out on a time axis along one wall. On another the TV was playing a very well made Kanazawa tourism ad promoting the colourful and varied four seasons of the city.

Outside the visitor centre was a short patchwork segment of wall. It was specially constructed using four different ways of wall building, used for different walls throughout the castle. Course irregular rocks used in wall foundations; square cut rocks for the upper walls and gate buildings; there were tiled walls; another was plaster on wooden frame and reed straws.

If time permitted, I would have liked to have gone on one of the rock wall touring route suggested by the castle guide pamphlet to check out all the different applications of wall buildings. As it was all I had time for was a short walk around the inner courtyards and snapping a few photos of the closed storehouses and the gun slits in the walls.

There was something magical about the white facade of buildings and walls in the sunlight before twilight, as if seeing into the past itself. A glorious melancholy of witnessing a past of lords and honor.

The plan for the evening was to go back to Higashi Chaya for some night time touring.

I was running only on excitement at this point, barely holding together after a whole day’s walking and biking. In times like this I tend to start making mistakes, the brain unable to pause to consider things in full for weariness would overtake it.

Too tired to find a restaurant, I went back to Katamachi where I saw a McDonald earlier in the day. As it had become by now, McDonald was my go to quick fix when I could not be bothered to work out where to eat.

There were no specialties menus on, which was disappointing. I ordered the teriyaki meal then went upstairs and found a seat. Glad to be finally sitting down, I grinned abit to have understood the staff asking if I was eating in or that was all I’m ordering.

I had some trouble finding the Korinbo bike station, partly due to poor marking on the map and partly because visibility was poor at dusk. Eventually I located it behind the Daiwa department store.

The ride to Higachi-Chaya was long. I wanted to get there before Hakuichi closed, determined now to get the ukiyoe gold foil print.

Pass the bridge and down the small street, I stopped in the courtyard at the entrance of the Chaya district and where Hakuichi was located. It was closed.

Tomorrow then.

The warm glow of the lanterns cast no shadows in the murky blue surrounds. The lights of the shops and teahouses shone through the slits windows like portals to a fanciful world.

Some of the teahouses here still operated at night and it’s said that when the night deepens the street becomes filled with music and cheer. Can’t say I feel the liveliness. There were plenty of tourists enjoying the atmosphere of the old district in the evening, it was one of a still pond of serenity.

After some time I headed back to the hotel reluctantly.

I stopped by the bike station to swap the bike, then I realized that I should have also swapped the bike on my way to the chaya district. As it was I had exceeded the 20min free period and would be charged for a small fee.

I was smarting about the mistake while riding, which was probably why I then took a wrong turn at the Musashigatsuji intersection. I did not notice at first, but after a few minutes of the area turning more and more residential, I pulled out google map and saw my mistake. As a result it took me another 10 minutes before I got back to the hotel.

After a shower things began to feel a bit better. It was near 8 and my stomach was starting to feel empty.

Thankfully I had a long list of candidates and knew precisely what I needed. Vegetables.

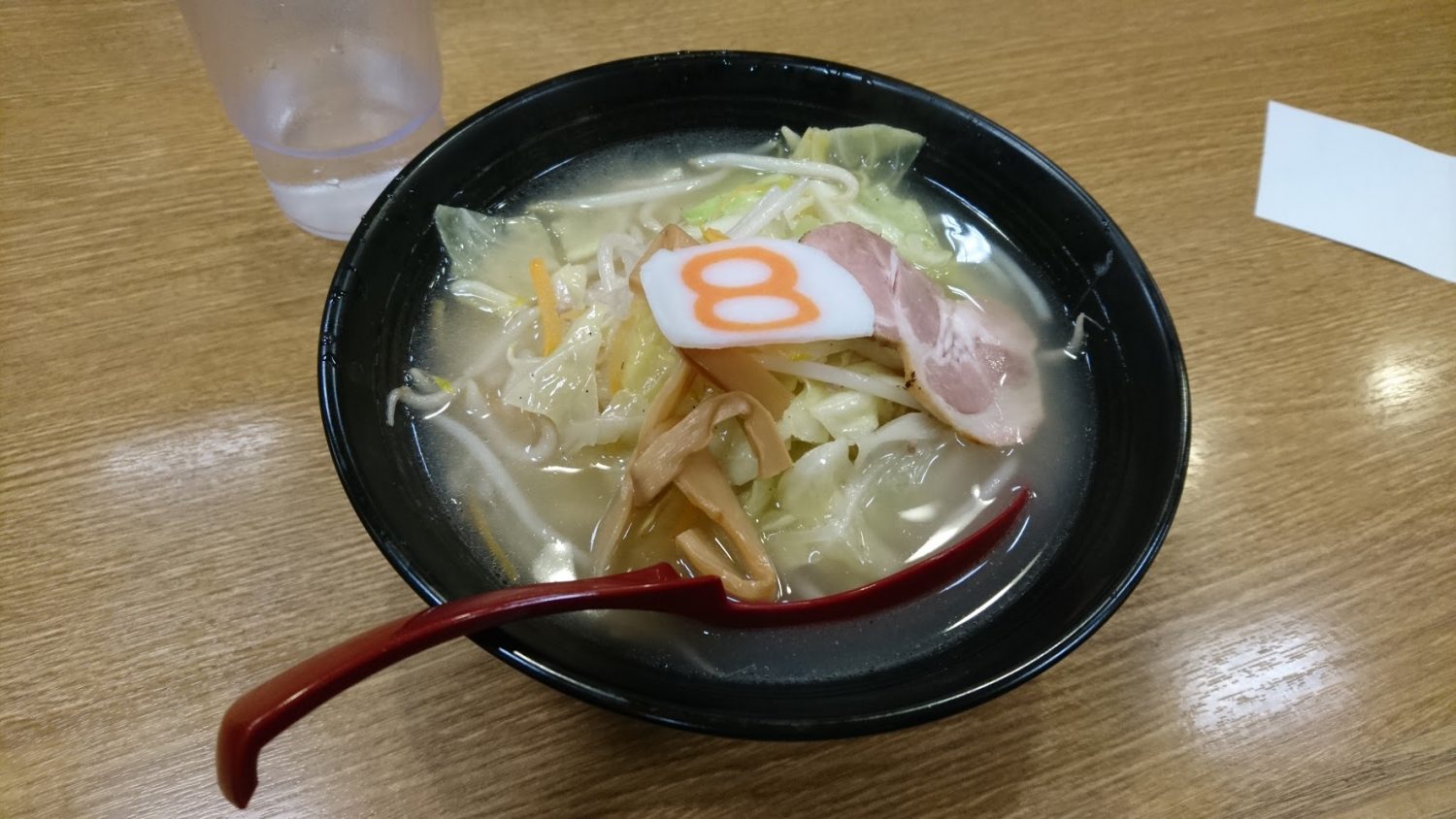

Ever since discovering champione noodles back in Hakata, I have found a balanced diet is the key to keeping the body from getting upset. Vegetables aren’t the easiest thing to find on the eat out menu but there was one in the restaurant street in the station. Number 8 Ramen. A place the specialized in heaping plenty of vegetables on top of a bowl of ramen, much like Ringer Hut’s champion noodles.

It was a good thing the hotel was so close, if it had been any further I might not have worked up the will to venture out. Past evening rush hour the station was not terribly busy and the gift shops were closing up. It took me a full circle before finding Number 8 Ramen.

I ordered the yasai ramen (green vege ramen) which claimed to have half the daily recommended greens intake. It’s about 640Y, on the cheaper end for a bowl of ramen, at least compared to the big cities. Ramen might generally be cheaper here.

The place was half full. While I was lost in the restaurant streets I noticed that other than the sushi shop and izakaya, the rest were generally not packed. The former attracts more tourists and the later probably more office workers, leaving the remainder a middling unnotable bunch.

There was a giant logo on the wall and slogans promoting the history of the shop. It was nice and clean, the lighting bright. The decor was akin to Ringer Hut or similar non-traditional ramen shops that aims for a more family friendly atmosphere.

The noodle itself was more salty than Ringer Hut. It was a ramen after all, still much lighter than regular ramens. There was a generous helping of cabbages and beansprouts as promised, a small slice of meat and nice white noodle of above average thickness. Nothing eye opening, just good solid taste.

Satisfied, I finally went back to the hotel and concludes the long day.